Kosovo Virtual Jewish History Tour

Though a relatively recent independent country, Kosovo can trace its Jewish history back to the 15th century when Jews first started coming to the Balkans.

Though a relatively recent independent country, Kosovo can trace its Jewish history back to the 15th century when Jews first started coming to the Balkans.

Early History

The arrival of Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Spain and Portugal in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries marked the beginning of the community in the Balkans, which was under Ottoman rule at the time. Sultan Bayezid II welcomed the Jews into his empire, where they became involved predominantly in the salt trade.

Prior to this, there are no records of any Jewish community residing in the Balkans. The earliest mention is in the 1455 Turkish cadastral tax census of the Brankovic dynasty lands (comprising 80% of present-day Kosovo), which recorded one Jewish dwelling in Vučitrn.

However, the remains of one Europe’s oldest synagogues, dating back to Roman times, is believed to be among the ruins at Ulpiana, which sits just outside the present-day capital of Priština.

Records indicate there may have been as many as 3,000 Jews living in Kosovo in 1912. But it was around this time, after Serbia conquered Kosovo, that their fortunes began to change.

The World Wars & the Holocaust

After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the boundaries of the Balkans shifted. Serbia merged with Montenegro, and then united with State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which was soon renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The largely Albanian-populated Kosovo was included within Serbia. At the time, some 500 Jews resided in Kosovo.

By 1921, a population census recorded 427 Jews living within present-day Kosovo.

Yugoslavia surrendered to Italian forces on April 16, 1941, and subsequently Kosovo became a part of Greater Albania. After Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943, Nazi Germany took control of Kosovo, but it again exchanged hands in 1944, when the territory was recaptured from Albania and made a part of Yugoslavia.

Under Italian rule, Kosovo became completely integrated into Albania, both politically and culturally. Albanian was declared the national language and schools were established; an Albanian police force was created; the Albanian Lek became the official currency; and Albanian newspapers and radio stations emerged.

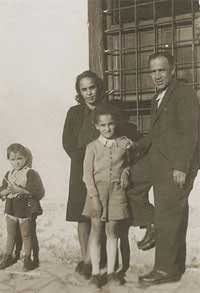

Jewish refugees pose outside the Priština prison. In April 1941, Kosovo Serbs were attacked and forced to flee. Businesses and homes were destroyed, cemeteries desecrated, and mass executions were committed against the Kosovo Serbs.

In 1942, an internment camp was built for Jewish refugees from Serbia in the city of Priština. They were held there for 10 months. They had originally been placed in an abandoned school before they were moved to the prison. Jewish families were allowed to stay together in family units, but were separated from the other prisoners. They were allowed to go in the courtyard during the day.

When the Jewish prisoners formally complained to the authorities about the overcrowded conditions, the Germans responded by executing half of the prisoners. Soon after, the Italians removed the remaining Jewish prisoners after several German demands to do so, and transported them by truck from Priština to Kavaja in Albania proper. Fifty-one Jewish prisoners were turned over to the Nazis, and were later killed.

By July 1942, the Italian police arrested the remaining Jewish families left in Pristina; five families were sent to Kavaja, where they were forced to report to the police station every day.

The situation intensified when Nazi Germany took over in 1943. Serbian houses were robbed and looted. Orthodox priests were attacked and murdered and orthodox churches were ransacked. Nearly 600 Serbs were arrested and sent to prison in 1943.

When Nazi Germany took control of Kosovo in 1943, they sought to exploit Albanian nationalist ideology that was created in 1878, which called for an ethnically Albanian Kosovo, and created the 21st Waffen Gebirgs Division der SS “Skanderbeg,” on April 17, 1944. The Skanderbeg Division was made up mostly of ethnic Albanian troops, two-thirds of whom were Kosovars.

In 1944, Albanian fascists, acting on Gestapo orders, interned and plundered the belongings of 1,500 of Priština’s Jews, most of whom were sent to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Post-war

Less than half of Kosovo’s pre-World War II Jewish population of 1,700 survived the Holocaust. Most of those that did emigrated to Israel from 1948 to 1952.

In 1941, about 550 Jews lived in Kosovo. It is estimated that about 200 Jews from Priština were killed in concentration camps.

|

|---|

The synagogue was destroyed and never rebuilt. Documents and papers in the Jewish archive were burned, never to be replaced. Homes and businesses were looted and property seized. Jews were forced to wear the yellow armband in some parts of Kosovo. The Jewish presence that dated back over five centuries was virtually demolished. Only a handful of Jewish families remained.

In the aftermath of World War II, an organization was founded to help the remaining Jews of Yugoslavia immigrate to Israel and to generally coordinate the affairs of all the communities. It was called the Federation of Jewish Communities in Yugoslavia, and was headquartered in Belgrade. More than half of those surviving Yugoslav Jews chose to leave for Israel.

The Jewish community of Serbia remained under the umbrella of the Federation, along with several other Jewish communities in the territories. The lived relatively peacefully from World War II until the 1990s, with the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Jewish Community Today

There are only about 50 Jews left in Kosovo, that belong to three families, or clans as they are called. They all live in the city of Prizren.

At the start of the Kosovo War in 1999, the Serbian-speaking Jews living in Kosovo in the capital city of Priština, fled to Serbia or Macedonia. But those living in Prizren stayed (they speak Albanian and Turkish).

The head of the Jewish community at the time in Priština, Čedomir Prlinčević, said he and the other Jewish families and non-Albanians were forced to flee by Albanian paramilitaries, who either believed they were Serbs or had collaborated with them, during a 10-day period in June 1999, with the help of the American Joint Distribution Committee. According to Prlinčević, the gangs showed up at his apartment with machine guns, and told him to leave the house or they would “slaughter” him. He and his wife eventually resettled in Belgrade.

Many of the Jewish population of Prizren are poor and unemployed. With the advent of Kosovo’s independence, the future appears even bleaker for the Jews, who remain on the outside in a quasi-state controlled by ethnic Albanians. Many are pessimistic. Leaving their homes and “aliyah” to Israel is now a significant contemplation.

This small Jewish community is supported by the American Joint Distribution Committee, which provides the necessary social services, helps with employment, and also hosts celebrations on Jewish holidays, which used to hold an annual Passover Seder.

Other projects of the American Joint Distribution Committee included revitalizing the Kosovar educational system, in addition to protecting the small Jewish community that remained there after the 1999 war, which devastated the society. Humanitarian efforts are also of great imperative and the JDC has worked to reconstruct and equip schools, providing computer and vocational classes, as well as projects aimed at fostering religious and ethnic coexistence.

Operations have significantly been scaled back in recent years, as Kosovo’s remaining Jews make their way to Israel or elsewhere. Some remaining Jews in Kosovo are hopeful about the future, as the government tries it’s best to show support for the dwindling Jewish community that is left. Current Jewish community president Votim Demiri is well known locally and active in politics. He ran a textile factory during “the good times” that had over 3,000 employees and his daughter is a foreign ministry official. Demiri is currently in the process of trying to get the government to invoke eminent domain and take back sites that were historically Jewish but have been converted and changed purpose over the years. His hope is to build a stronger Jewish community in Kosovo where 90% of the population is Muslim, starting with a local Jewish Community Center in Prizren.

Israel has good relations with the Kosovars, with Jerusalem sending massive humanitarian aide to the besieged Muslims during and after the 1998-1999 war with Slobodan Milosevic’s regime. At the same time, it also has strong economic ties with Serbia, and is reluctant to recognize the Republic of Kosovo, until it receives more international recognition, including that of the United Nations. Israel is hesitant about recognizing Kosovo at this time because they are worried about the way the Kosovars unilaterally declared independence. The Israeli officials fear that recognizing a country that came into existance this way would validate the plight of the Palestinian people and their want for their own independent state. Kosovar officials speak of a long and collaborative history with the Jewish people, who rallied support for the Kosovar people during the war in 1998-1999. American Jews have constantly supported the Kosovar’s struggle for independence, and Israeli Jews have provided aid and material support to the people of Kosovo. Kosovar officials see this support and consistently wonder why Israel is not one of the 110 countries that recognize Kosovo, claiming that Israel’s recognition is symbolic, and demonstrates validation of their partnership.

Sources:Dinah Spritzer. “Kosovo’s independence comes amid uncertainty.” JTA (February 17, 2008).

Wikipedia, “History of the Jews of Kosovo.”

Milovan Mracevich. “Targets of terrorism, Pristina’s Jews forced to flee.” The Globe and Mail (August 31, 1999).

Ted Siefer. “Last Seder in Kosovo?” Ha’aretz (April 21, 2003).

“Driven from Kosovo!” Interview with Čedomir Prlinčević, Chief Archivist and leader of the Jewish Community in Priština, capital of Kosovo province (Serbia). Interviewed

by Jared Israel and Nancy Gust, The Emperor’s New Clothes (September 9, 1999).

Photos courtesy of USHMM. Top photo: Group protrait of the children of Jewish refugee families incarcerated in the Priština prison.

Source: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/kosovo-virtual-jewish-history-tour