With US help, Muslim-majority Kosovo plans its first synagogue and Jewish museum

Though today home to just under 60 Jews, the state — which vies for international recognition — boasts a community that dates back to prior to the Spanish Inquisition

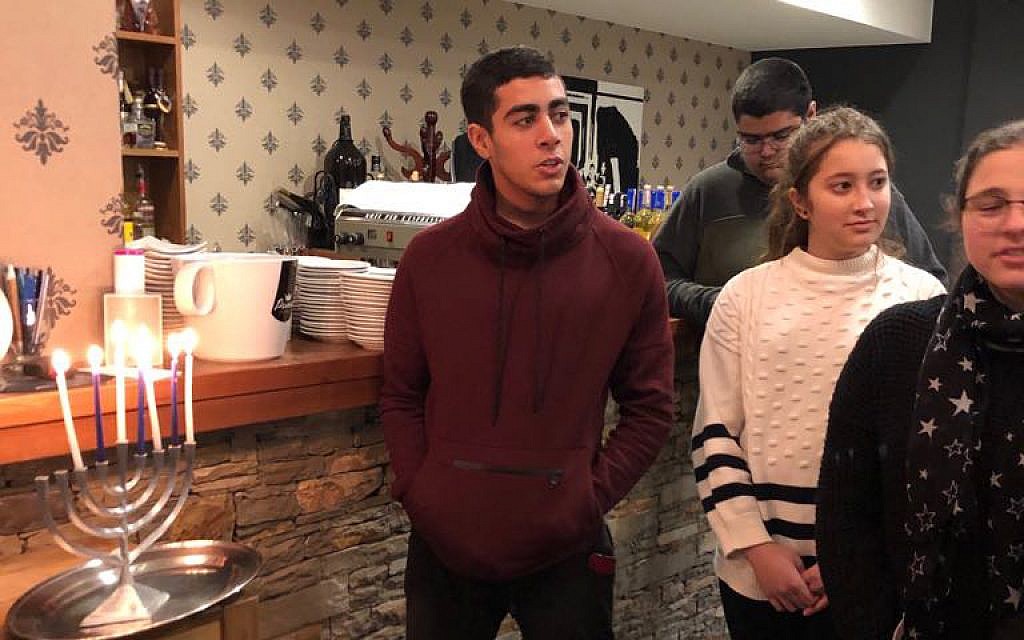

PRIZREN, Kosovo — Earlier this month, about 40 people gathered at a Catholic-owned hotel in Kosovo’s second city to light the sixth candle of Hanukkah.

The Friday night ceremony was jointly organized by Votem Demiri, the 72-year-old patriarch of Kosovo’s tiny Jewish community, with help from Dr. Irfan Daullxhiu, a Muslim cardiologist in Prizren, and Steven Aiello, founder and co-director of the Arab-Israeli nonprofit group Debate for Peace. About two-thirds in attendance were local Albanian-speaking Jews and Muslims, and the rest visiting students from Israel.

It marked the latest in a series of Jewish events in this medieval Balkan stronghold far more famous for its Ottoman-era Sinan Pasha Mosque, and its 19th century Cathedral of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour, than for anything even remotely connected to Judaism.

Within a year, Prizren could also boast a new kind of religious landmark: Kosovo’s only synagogue and Jewish historical museum.

The proposed “Muzeu Shqiptaro-Hebraik,” or Albanian Jewish Museum, will stand out in a country where more than 95 percent of its 2 million inhabitants identify as Muslim.

“I want to have a religious building that’s open for everybody,” Demiri told The Times of Israel earlier this year. “I expect even schoolchildren to visit. Through artifacts and photographs, we will explain the history of the Jewish community. We are collecting these artifacts now.”

Daullxhiu, who visited Israel in 2007 for a medical conference, supports the museum too.

“I think it’s a very good project for our city and also for Kosovo, because the Jews are part of our history,” he said. “Unfortunately, at the beginning of World War II, practically the entire Jewish community left Kosovo.”

Today, Albanian-speaking Kosovo — the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined — is home to only 56 Jews, 14 of them children. Nearly all reside in Prizren, a quaint, compact city bisected by the picturesque Bistrica River flowing under graceful stone bridges.

A history of warm relations across the region

In medieval times, Prizren was the capital of the entire Serbian Empire. During WWII and until the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991-92, Serbia was the largest of the six republics that made up the Yugoslav federation.

About 3,000 Jews now live in Serbia, which controlled Kosovo until the latter’s unilateral declaration of independence in 2008. Hardly any remain in Albania, whose predominantly Muslim population hid the country’s 200 Jewish citizens as well as another 600 to 1,800 Jews from neighboring countries during the Nazi occupation.

“There are so many examples of [Albanian-speaking] people rescuing Jews,” Demiri said, citing the example of Arslan Resniqi, a Kosovar Muslim who in 1941 smuggled a Macedonian Jewish doctor out of a Nazi POW camp. In 2008, following a campaign by the doctor’s granddaughter, Israel’s Yad Vashem honored Resniqi as Righteous Among the Nations.

Demiri, who smokes two packs of cigarettes a day despite his numerous bypass surgeries, prides himself on his vast knowledge of Jewish and Balkan history. From 1988 to 1992, he lived in Paris, representing the Yugoslav Chamber of Commerce in France. Before that, he ran a textile factory that employed 2,600 workers and was Prizren’s most influential businessman.

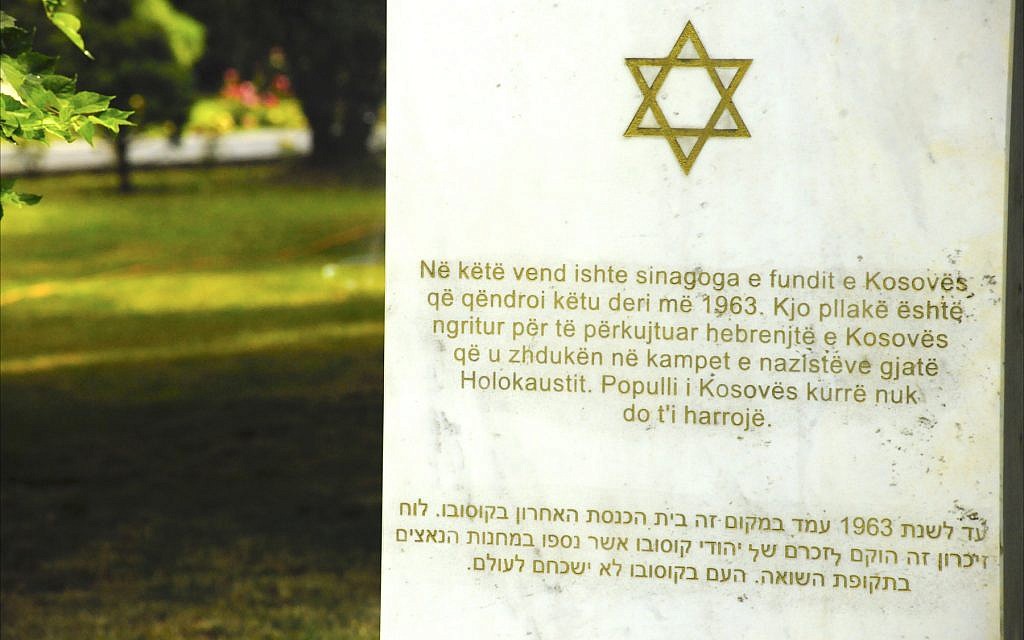

The retired grandfather, whose conversation is constantly interrupted by friends stopping in the street to greet him, sadly recalled the day in 1963 when Kosovo’s only synagogue was demolished to make way for the new Parliament building in Priština.

“I was 17 then. I remember my mother crying when she heard the news,” he said. “At that time, I didn’t understand what was going on.”

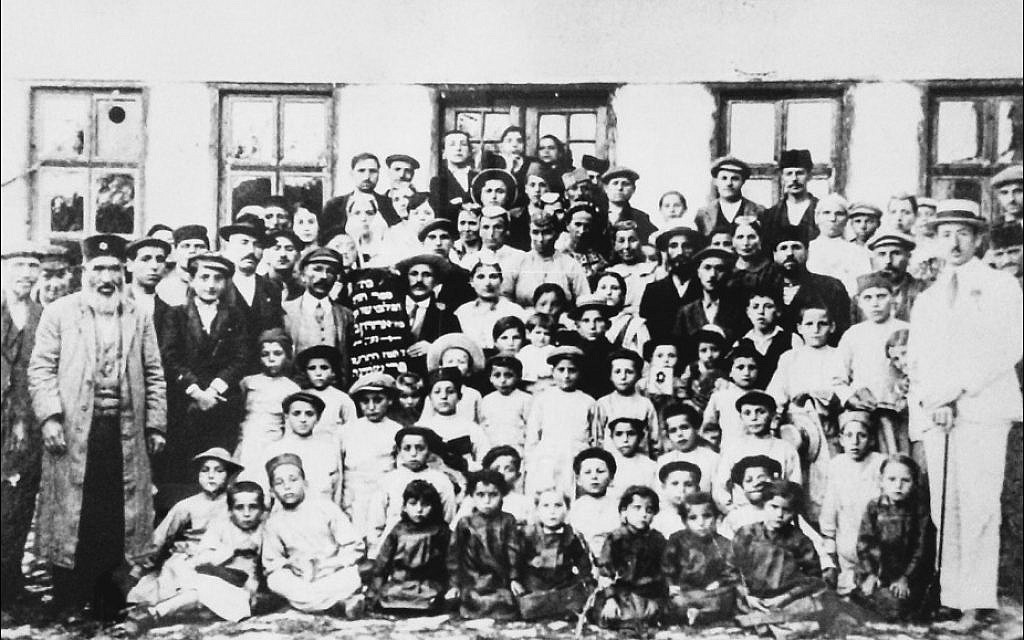

Demiri displays a 1929 black-and-white photo of that long-gone shul and its congregation — along with more recent pictures of himself with former US vice president Joe Biden, former British prime minister Tony Blair and other dignitaries — in the “Jewish room” of his house, which also contains Hebrew prayer books, an upright piano and a Hanukkah menorah.

“We do Shabbat every Friday in my home for now, but sometimes we have a problem getting a prayer quorum,” said Demiri, whose son lives in Kosovo; he also has a daughter in New York and another in Tel Aviv.

Occasionally, local Jews have been joined by others from Subotica (in northern Serbia, near the Hungarian border) who traveled by bus to Prizren for the weekend.

Project earns backing of US Jews, Muslims

From Demiri’s house, it’s a five-minute walk along a cobblestone path to the Ambient Restaurant, which hosted this year’s Passover seder for 100 guests. It’s another 10 minutes to Rruga Hysen Rexhepi; on this street sits Prizren’s future Jewish museum and synagogue.

The decrepit building, formerly an old-age pensioners’ home, is located next to the Red Cross of Kosovo and directly across from the Catholic church, whose bells chime loudly as the chanting of a muezzin is broadcast from a nearby mosque.

Upon completion, the two-story complex will measure 300 square meters (3,230 square feet) and cost around $300,000. Kosovo’s Ministry of Culture has allocated 50,000 euro (about $59,000) for the project, with renovation beginning early next year; its benefactors hope to finish by the end of 2019.

Plans call for the museum to occupy the first floor. On the second floor will be a synagogue, open for Shabbat and festivals. Admission will be free, with all exhibits labeled in English, Albanian and possibly Hebrew.

To bring the project to life, local Jews are working with the municipality of Prizren, as well as the World Jewish Congress and the American Joint Jewish Distribution Committee.

Rep. Eliot Engel, whose New York congressional district includes a large Albanian ethnic population, is the incoming chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. Earlier this year, the New York Democrat visited Prizren along with two Albanian-American businessmen of Muslim origin: Harry Bajraktari and Rustem Gecaj. Next February, Bajraktari will host a New York City fundraising event at which they hope to raise between $50,000 and $100,000.

“I’m so excited about this project,” said Bajraktari, a Bronx real-estate developer. “Prizren is a symbol of resistance against the Ottoman Empire and is home to many religions — the Catholics, the Orthodox, the Muslims and the Jews. It’s a great place for the museum. We believe it will contribute to the people of Kosovo and future generations.”

‘A synagogue isn’t a synagogue if it has no people to pray in it’

Landlocked Kosovo, conquered by the Byzantines in the Middle Ages and subsequently ruled by the Bulgarians, the Serbs and the Ottomans, is today one of the most pro-American countries on Earth. A 10-foot statue of former president Bill Clinton fronts a boulevard of the same name in Priština, and in November 2017, Kosovo’s post office issued a 2-euro stamp featuring Engel — the first time in living memory a US congressman has been so honored.

As a lawmaker, Engel pushed hard for the Clinton administration to intervene in the late 1990s against Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic, who had engaged in ethnic cleansing against the Kosovars.

Despite its status as Kosovo’s capital and largest city, Priština today has little of Jewish interest except for a hillside cemetery with 75 or 80 gravestones in various states of disrepair.

“To tell you the truth, there are very few Jews in Priština,” said Fatos Jusufi, 42, a local barber who learned Hebrew from his mother but rarely gets a chance to speak it. “No more than 10 Jewish families live in all of Kosovo. I know very well who’s a Jew and who’s not.”

Priština also has a marble monument on the grounds of parliament — engraved in Albanian, Serbian, English and Hebrew — that marks the spot where the synagogue stood until 1963. An inscription on the monument also honors the 258 Kosovar Jews whom the Nazis deported to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, 92 of whom were killed there.

Demiri said that Kadri Veseli, chairman of Kosovo’s parliament, initially proposed opening a synagogue on that spot, but eventually understood that the idea made little sense.

“I was against putting the synagogue in Priština from the first day,” said Demiri. “Hardly any Jews live there, and it’s not so easy for us to travel to Priština from Prizren every Saturday to pray. A mosque is not a mosque — or a church a church, or a synagogue a synagogue — if it doesn’t have people to pray in it.”

No diplomatic recognition from Israel — yet

On February 17, 2008, Kosovo — a province of Serbia that had enjoyed some degree of autonomy as long as Yugoslavia existed — unilaterally declared independence, infuriating the Serbs. In the 10 years since, 116 nations have recognized Kosovo, including 23 of the European Union’s 28 members. The five EU holdouts are Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Spain and Slovakia.

Israel has so far resisted extending diplomatic recognition, though on September 21, Kosovo’s president, Hashim Thaçi, vowed that if it did, Kosovo would set up an embassy in Jerusalem. Among other things, Israeli officials don’t want to offend Serbia, with which it has strong ties. They also don’t want to set a precedent for recognizing unilateral declarations of independence, given Israel’s current impasse with the Palestinians over a two-state solution.

Teuta Sahatqija, Kosovo’s ambassador to the United Nations since early 2016, said she’s proud of the religious harmony she says exists in Kosovo.

“For us, it’s very important that, through this museum, we will show friendship and respect for our Jewish citizens. They are also Kosovars, and we appreciate them,” said Sahatqija, interviewed at a Priština café a few blocks from the Holocaust memorial plaque.

In late 2016, Thaçi banned all anti-Semitic literature in Kosovo after a visiting Israeli expert on racism and terrorism found dozens of neo-Nazi books — including three Albanian-language translations of Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” — on sale at a Priština street market. And earlier this year, a court in Priština sentenced eight Kosovars to jail for planning a foiled attack against the Israeli national soccer team during a 2016 qualifying World Cup match in Tirana.

Yet Kosovo’s warmth toward its Jews hasn’t yet translated into recognition by Jerusalem.

“The Israelis never said so clearly, but their fear is that it might resemble the issue of Palestine,” Sahatqija complained. “But this has nothing to do with Palestine. Kosovo is a product of the dissolution of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It’s the seventh state. Everybody already recognizes six states, so it’s unimaginable why they don’t recognize the seventh.”

Kosovo and Serbia are negotiating a land swap that involves exchanging bits of territory based on the ethnicities of local inhabitants, though nationalists on both sides oppose the idea.

Demiri says a resolution of the longstanding dispute with Serbia could open Kosovo to Israeli tourism and investment — as well as a resurgence of interest in its Jewish past.

“Both Kosovo and Israel are young nations, and both are surrounded by a hostile environment. But both managed to overcome these challenges, thanks to strong friends like the United States,” he said. “I’m telling you, it’s only a matter of time before Israel recognizes us.”

https://www.timesofisrael.com/with-us-help-muslim-majority-kosovo-plans-its-first-synagogue-and-jewish-museum/